| Standing Stones In Sussex |

[ Earth Mysteries Page | Sussex Main Page ]

| Introduction | |

|

Introduction Sussex is not well known for standing stones. Aubrey Burl doesn't list any Sussex stone circles in his books, there are no chambered tombs and whatever is left has been taken for building material, as there isn't much in the way of decent building stone in Sussex. But like the downland of Wiltshire, famous for its stone circles, the downland of Sussex also has its share of sarsen stones, some of which have been used in ancient times. While there is no definite proof of the existence of megaliths from the time of the stone circles, it is not unlikely that they existed on the Sussex Downland. Most sarsen stones have been removed from farmland to stop them getting in the way of ploughing. They have found their way into villages and around ponds. The high level of land use in Sussex has destroyed any evidence of what might have been. Nevertheless, there are many modern stones which have attracted folklore of the type normally associated with more ancient standing stones and of course a slew of stones associated with Druids by early antiquarians. I would like to thank Bob Brown for his help with references for this page. Geology sarsen stones, or Greywethers were formed mainly in the Eocene and are a form of sandstone (SiO2) with a small amount of impurities (Jones 1981 p.98). In Sussex, many of the stones have a reddish tinge as they have Iron impurities. They are generally found on the tertiary beds above the chalk, so are generally only found on the chalk downs and the coastal plain below. It is still a matter of contention whether the downland stones are glacial erratics or natural deposits as is thought that the glaciers stopped around the area of the South Downs. Some people believe that Devil's Dyke is a glacial valley. Another source of these stones is the Wealden Sandstone spur, where outcroppings were used by ancient people as rock shelters when they hunted in the weald. This sandstone lies under what would have been a huge dome of chalk, which the North and South Downs represent the edges. The centre of this dome was eaten away by the sea in previous eras, leaving the South Downs of Sussex with old eroded cliffs facing north into the weald and the more gentle slope of the leading down towards the coastal plain and the sea. Rivers and streams have cut through these last remains of the great dome, leaving the once buried tertiary rocks exposed and weathered in the downland valleys. Though they are to be found all over the South Downs, these stones are most common between the Rivers Ouse and Adur. Map

|

| Sites | |

|

Rest And Be Thankful "Rest And Be thankful" is the name of a stone that rests along the track between Southwick and Thunders Barrow (TQ239070). It is a block of sarsen stone measuring roughly 3 feet square and 2 feet high, and makes an excellent seat, which is probably where it got its name. The stone was apparently moved here from Southwick Church where it was originally built into the fabric of the church, but when the wall was widened in the 19th century, the stone was brought here to be used as one of the boundary stones along the trackway (Holden 1976,Holden 12/13). Most of these boundary stones, of which many more were marked on earlier Ordnance Survey maps, are now missing. There is an interesting hollow on the top of the stone which Eric Holden thought might be a flint axe polishing surface.

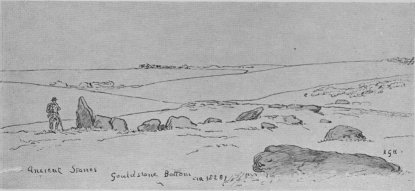

The Goldstone Near Hove stands a very large block of stone called The Goldstone (TQ287060), which gives its name to an area known as Goldstone Bottom as well as the now destroyed Goldstone football stadium. The stone is roughly 13½ feet long, 9 feet high, 5½ feet wide and estimated to weigh about 20 tons. Surrounding this large stone are a group of much smaller stones arranged in a circle around it. These stones and the Goldstone itself are formed of a sandstone/flint conglomerate, but neither the Goldstone or the circle are in their original positions (Toms 1932 p.725). The Goldstone itself once stood to the South-West (TQ285059), just South-East of the present A270/A203 crossroads. The view in Fig. 1 is of the stone on open downland dated roughly between 1820-1830 (Martin 1931 p.152). In 1833, Farmer Rigden, who held the land as part of Goldstone Farm, decided to remove the stone as visitors were damaging crops when visiting it, so he dug a large hole and buried it (Middleton 1979 p.29. In 1900 however, the stone was found, brought to the surface and re-erected in the same manner that it stood before but 300 yards away, in what is now the corner of Hove Park. The stones currently arranged around The Goldstone came from a spot further north in Hove Park (roughly TQ288066). Fig. 2 shows a view of these stones around 1828, when they were arranged around a pond (Toms 1927 p.532). The group of stones on the left next to the shepherd seem to have been arranged standing instead of laying about in a haphazard manner. This group of stones was removed for farming purposes around 1847. Some of the stones were buried in the pond which was filled in at the same time (Toms 1932 p.726). The stones in the pond were exhumed in 1906 and arranged around the Goldstone in its present position. This was done by a Mr. W Hollamby with the help of named Terry who had helped bury the stone in the first place (Martin 1920 p.105). One author suggests that the stones around the Goldstone are formed of stones from no less than two stone circles (Evans 1935 p.60) Such an impressive local feature as the Goldstone in bound to attract folklore. On an 1858 map of Brighton, the stone is named as "Godstone". This name may have come about because one side of the stone has the form of a human face. Figs. 3 & 4 show a view of the face on the stone along with a sketch of the same view. The feature is purely natural, there is no sign of carving (Toms 1932 p.728). As to where the stone came from, folklore also has the answer. The stone was thrown to its present position by the Devil when he was excavating Devil's Dyke to let in the sea through the Downs and drown the population of the weald (Wales 1992 p.63). Finally, the stone is popularly known as the site of a Druidic Gorsedd, but this is probably just modern fancy. A sign next to the Goldstone tells us that it is a "Tolmen or holy stone of the Druids"! Though it is debatable whether ancient druids use the site, more modern druids certainly have. On the 3rd June 1929, an oak tree was planted near the stone to commemorate the King's recovery, also to commemorate the 1000th night of the Ames Lodge and the 100th chapter of the Brighton & Hove Royal Arch (Ancient Order of Druids). The ceremony and a banquet afterwards was attended by many important figures in Druidism of the time (Holden 12/12) and a plaque was placed nearby to commemorate the occasion (Ashton 1980 p.17). |

Fig. 1 : The Goldstone circa 1820 |

Fig. 2 : Possible Stone Circle in Goldstone Bottom |

Fig. 3 : Sketch of the Goldstone showing the face |

Fig. 4 : Photograph showing the face on the Goldstone |

|

St. Nicholas Church, Brighton On the top of a hill in Brighton is the Church of St. Nicholas. When Brighton was still young fishing village, the church was isolated from the rest of the community and stood alone on the hilltop. Now, part of Brightons sprawl, there are still tales remembered about the past of the church. According to local folklore, the church was built on the site of a stone circle (Aitchison 1926 p.104). Horsfield writes that he examined three stones when he visited the church and was told that there had been many more, as well as a tumulus known as "Bunkers Mound" (Horsfield 1835 p.106). By the late 19th century, these last stones were gone (Clarke 1882 p.34) and one writer suggests that many were used to surround the pump on the Old Steyne in Brighton (Sawyer 1879 p.199). Though the stones are nowhere to be seen, the ghost of a white horse can sometimes be seen galloping around the church at night. Some versions of the tale gave the horse a ghostly rider and some say that its bones were found when the first electric cables were put in (Wales 1992 p.20). The Old Steyne, Brighton When Brighton was still small, this area of land was on the eastern edge of town. It is now bounded by busy roads and little is left open. The name of the place echoes the memory of the many stones that used to be found on this area of the coastal plain. On this piece of land once stood a fountain surrounded by sarsen stones. While some people have hailed this as the remnants of an ancient site, it is far more likely that these stones were put around the fountain to keep them out of the way of agricultural or building projects. It has already been mentioned that some of the stones buried near the Goldstone are thought to have been moved here, and it is also thought that some of the stones that once stood around St. Nicholas church were also moved here, though according to the Rev. Evans, there were already plenty of sarsens in the area, as it used to be the base of a valley for an old stream called the whales-bourne, which was littered with boulders (Evans 1933).

Still in existence on the Old Steyne is a fountain which is surrounded by some of the old stones. Some people think the fountain is on a major ley-line that runs along the "spine" of the town and the stones are remnants of a stone circle. A spiritual group was set up in Brighton during 1981 using the fountain as a focus and have become international. Visit their web site at : www.fountain-international.org. Aldrington Church Not too far west of St. Nicholas Church in Brighton, is St. Leonards Church in Aldrington. It lay ruinous for a long time, finally being rebuilt in 1878 and 1936 (Mogar 1973 p.276). The accompanying picture (Bull 1929 p.838) is of the church in a semi-ruinous state, it became much worse before being rebuilt. The woodcut is very old, take note of the four uncarved stones in the foreground. Another author, describing a sarsen stone found in Sussex says "Similar stones may be seen in the NW. corner of the churchyard of Aldrington Church, Hove" (Barr-Hamilton 1970 p.15). There are five blocks of sarsen stone in this corner of the churchyard, which look like the four shown in the woodcut along with one other small one. The two largest are shown in the photograph.

Big-Upon-Little The centre of the Weald is dominated by a sandstone ridge, which occasionally bears itself as large outcroppings. One such outcropping on a private estate and near the villages of Ardingly and West Hoathly is formed of cliffs in the shape of a V. A bank of earth connects the top of the V and the whole is known as Philpot's Promontory Camp (TQ350323). It is assumed that the camp dates from somewhere in the Iron-Age (Hamilton & Manley 1997 p.105), though quantities of flintwork, including Mesolithic, has been found at the site (Tebutt 1974 p.41). Two sandstone blocks set apart from the cliffs are of interest. The first is known as "Big-Upon-Little" or "Great-Upon-Little", which is a large block of the natural sandstone which is quite close to the cliffs, but has been separated by the action of water. The base of this stone has been eroded away by water and the stone above is now perched on a tiny stump of a base. Upon this stone, tourists in previous centuries have carved their initials and dates to the extent that most of the reachable surface has been carved and recarved in this manner. It was recorded in 1778 by a Mr. Thomas Pownall that the stone "was covered with multitudes and initials of all dates" and though he mentioned none, an initial and date of W.R. 1650 has been recorded (Holgate 1926 p.224). The second stone is known locally as the "Executioners Stone" but very little else is known about it. It is easy to see where the stone got its name from, as the large gash down the stone, which is over a foot deep, could easily be interpreted as a drain for blood. Local people have also mentioned that "Pagan sacrifice" happened at Philpots, they were probably referring to this stone.

'Druid Altars' At Rudgwick In the Lynwick Estate west of Rudgwick, there is a natural outcropping of sandstone (TQ07013380). They were marked on the estate sale catalogue of 1922 as "Druid Altars", most certainly a modern fancy. The stone has been sliced down the sides, probably a feature of quarrying, and may be the reason that the stones here have earned their title (Aldsworth 1983 p.212). Stanmer The name Stanmer, which is the name of a village north of Brighton, is derived from the Saxon "Stan" (stoney) and "Mere" (boggy ground). The ground is indeed boggy and if you visit the village, you will see many of the stones which give the village its name. While most of the sarsen stones placed around the village have obviously been moved from their original position, it is thought by some that a group of stones dug up from a field by a farmer near a piece of woodland known as "Granny's Belt" represent the remains of a stone circle. There are probably just naturally occuring stones though, and most of them currently sit in an isolated copse of trees within the field in which they were found (TQ335106). The picture is of the stones in the 1920's, of which only a few are left (Toms 1927 p.536).

Rocky Clump Somewhat more interesting is another copse of trees just west of Stanmer called "Rocky Clump" (TQ328102). The small copse of trees seems to have come about because there is a group of sarsen stones half buried on the spot, and it seems that a farmer at some point decided to mark off the area and not plough it rather than go to the trouble of removing the stones. There is indeed a ditch surrounding part of the site, though this was probably a later addition to an otherwise ancient site. The history of the site begins in the Romano-British period, where between the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, there was a some buildings in the vicinity. One of the naturally placed sarsens on the site is on the corner of one square building, of which several large postholes were found, which has been interpreted by some as the site of a Romano-British shrine (Gorton & Yeates 1988 p.8) but more recently thought is that this is just a farm building (Gilkes 1997 p.124). As part of recent ongoing excavations, a pit was found containing an ox skull overlying a bed of winkle and mussel shells, along with an ox skull overlying a bed of oyster shells (Funnel 2000 p.1). These were separated by a sarsen stone bearing tool marks. Similar finds of skulls over a bed of bones have been found in Sussex, including three such deposits in pits under the Romano-British shrine at Muntham Court near Findon, though the pit at Rocky Clump is not under the alleged 'shrine' building.

Following the Romano-British period, a small cemetery containing 7 bodies was placed on the site in the Middle Saxon period. The burials are aligned East-West with the head to the west and may have been placed here because the site is on some sort of boundary. A ditch which has been recut runs North-South through the site and is thought to mark either a manorial or parish boundary, which the stones here form a natural mark point for. The bodies may have been buried here on this boundary because they were executed criminals or other social outcasts (Simpson & Roud 2000 p.39). As an interesting aside, a field name just to the south of Rocky Clump is called "Patchway", which is thought to mean "the shrine or sacred place of an individual named Paeccel". Saxon holy names applied to more ancient sites are not unknown in Sussex with Harrow Hill and possibly Friday's Church, but this is still not proof of a Romano-British shrine. Only further excavation at the site can shed more light on its earlier use. Standean On the downs NW of Stanmer is Standean (TQ315115). The name means Stoney Valley and there are still stones about today. North of Standean itself is a pond known as "Rock Pond" with many large stones around it (TQ316121). Though one author believes them to be ancient (Martin) they are more likely to have been deposited there by farmers because they are a hazard to ploughing. The name Standean seems to be the most ancient thing about this place.

Falmer South-East of Stanmer is the village of Falmer (TQ354087). The village pump, which stands near the village pond, is surrounded by blocks of sarsen stone placed there at some point in history. The pond itself is lined in places by these stones, which have probably been moved from nearby agricultural land.

Steyning | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

St. Cuthman's Stone Though there is no conclusive proof of whatever stone or stones the name Steyning refer to, another stone is mentioned in old stories written about St. Cuthman, who is linked to the beginnings of the Saxon settlement at Steyning. St. Cuthman was born to Christian parents near the village of Chidham, West Sussex in the 7th or 8th century. He was given the responsibility of tending his fathers flock of sheep, and when he had to go and eat, he used to draw a circle around the flock and command them in the name of god to stay within the bounds of the circle, which of course they did. The stories also tell us this about the field in which the flock resided : "In the pasture there was a stone on which the holy shepherd was in the habit of sitting, which the locals still hold in great veneration today, for God brings many blessings through it by his merits" (Blair 1997 p.175). A possible location for this field is given in a Chidham glebe document dated 1635 which gives an acre of land south of Chidham as "St. Culman's feild" and within it, "St. Cullman's Dell". This field and the pond within it are at SU793027 (Blair 1997 p.181). When his father died, he took his infirm mother to what is now Steyning and built a wooden church there, presumably on the site of the current church, but that is another story. Ditchling Just below the northern edge of the South Downs lies the quaint little village of Ditchling. The village is built on a sandstone spur which rises to the North. The parish church of St. Margaret is built on a high mound of this sandstone and some people have suggested, as with many other Sussex churches, that it is an old Pagan site. The picture shown below-left is of a block of sarsen stone built into the southern churchyard wall, nicknamed the "Altar Stone" after some people suggested that it had been rolled off the top of the hill where the church stands. An inscribed brick in the wall is dated 1648, though parts of the church are pre-conquest. Many blocks of sarsen stone can be found in the village around the church. Several line the edge of the village green around the war memorial and the pond is lined with more, which have been placed in the water around the edge. Ditchling is also home to the only stone circle in Sussex, which is unfortunately modern. It is in the garden of a local farmhouse (TQ328154) and is built from local sarsen stone.

Alfriston The quaint old village of Alfriston lies within the Downs in the Cuckmere valley. Whilst the river Cuckmere has carved much of the Downland away in its course to the sea, many blocks of sarsen stone have been left, and used by the villagers. At the time of writing, sarsens were visible in a wall in West Street, as a kerbstone in North Street, three on the Tye, one in the churchyard, one in front of the Clergy house and and two at the base of the lion outside the Star Inn. Others were known in the past outside Dean's place, by a place called "The Spots" by the river (Pagden 1950 p.61). Climbing the Downs to the east, you may come across Lullington church, which is partially destroyed leaving only the Nave. Excavations on the destroyed portion of the church revealed a block of sarsen stone which had been built into the wall of the church in the 16th century (Barr-Hamilton 1970 p.15).

Hangman's Stone, Rottingdean A block of stone near the cliff edge at Rottingdean (TQ372021) has a curious story attached to it. To quote verbatim : "The legend goes that more than a hundred years ago, a sheep-stealer from Brighton walked to Saltdean and stole a sheep, which he controlled with a rope around its neck. He tried to lead it but when it grew fractious he started to carry it. When he reached the stone he stopped to rest, and began to lower the sheep from his back onto the stone. The sheep struggled and fell off the stone, and as it did so the rope was drawn tightly across the sheep-stealers neck and strangled him. He was found dead on the cliff top next morning, but the sheep was still alive, although tethered by the rope to the man which it had virtually 'hanged'" (Moens 1953 p.54). Another version of the story has the sheep stealer tethering the sheep to the stone and going down the pub. When he returned and fell asleep against the stone, the sheep managed to get the rope it was tethered with caught around the sleeping mans neck, strangling him in the process. The famous folk-singing Copper family have in previous generations taken advantage of this legend and sold stones which they claim to be the Hangman stone to unsuspecting people, for a hefty price! (Copper 1971 p.58).

A similar tale of the sheep stealer and other Hangman Stones are found in over a dozen places in England (Simpson & Roud 2000 p.165). The stone itself is a slab of a flinty conglomerate. In 1900, the stone was 50 yards from the cliff, in 1950 it is right on the cliff edge. As this page is being written in 2000, the stone is still there, probably due to improvements in the sea defences. Old maps show many stones in the area of Rottingdean marking out boundaries in land ownership on otherwise open sheep pasture. This may be another such stone, though it is not marked on the maps. Pevensey Tony Wales in one of his excellent books on Sussex folklore tells of a huge stone on the western boundary of Pevensey, which according to folklore was brought by an old woman as here contribution to the foundations of Pevensey Castle. On her way, her apron strings broke and she dropped the stone where it now sits (Wales 1992 p.73). Though Mr. Wales doesn't mention the exact location of the stone, it is possible he is referring to a large block of the wall belonging to the Roman fort, inside which the Norman Castle at Pevensey sits. Apronful's of stone are not uncommon in Britain, though they are usually applied to a group of stone, such as those in a chambered tomb. Grinsell believed the tradition to have migrated to England from Ireland (Grinsell 976 p.43). Is this the stone Mr. Wales is talking about, or is it located somewhere else?

Amberstone Northeast of Hailsham in East Sussex is a small hamlet called Amberstone (TQ598114). The few houses that make the settlement are set around a "bridge" on the A271, which was originally a ford over a stream that runs into the Pevensey levels. The stream now runs under the road but there is no perceptible bridge. The earliest form of the hamlet's name is Ambefeld, the first element being a Saxon personal name (Mawer & Stenton 1930 p.435). The name first recognises the place as a ford in 1212 with Ambeford then moves through Ombeford (1370) before the stone is first mentioned in 1470 with Ombefordstone. Finally in 1588, the ford element is lost leaving us with the Amberstone we have today. This stone is a real stone, and as the stream which is the focus of the hamlet once formed part of the boundary between the parishes of Hellingly and Hailsham, the stone is likely to be one of the Boundary stones. A piece of folklore has attached itself to this stone. "Local Tradition has it that at every full moon, and every time the clock strikes midnight, the stone turns round on its bed" (Wales 1992 p.48). This sort of legend is not uncommon, with stones running around, turning about and going down the local stream for a drink all over the country, usually at a certain time, as above (Grinsell 1976 p.56). The Smugglers Table In Charlton Forest, which stands on the northern edge of the South Downs near the village of Cocking in West Sussex, there used to stand a group of stones called "The Smugglers Table". This feature has now disappeared and replaced with a fir tree, but a local man said that the table was used by the smugglers to hide their casks of spirits (Beckett 1943 p.62). The description of this stones as a table and the ability to hide good inside it suggest that this may have been a dolmen like tomb. | ||||||||||

| Conclusions | |

|

sarsens Around Churches The extent to which old Pagan sites were Christianised is still a matter of great debate. One of the pieces of evidence we have is the presence of sarsen Stones in churchyards and built into the fabric of churches themselves. The question of whether these churchyards were just another non-cultivated dumping ground for stones is a difficult question to answer. It is certainly not an unlikely occurrence, but images such as the ancient woodcut of Aldrington church suggest slightly more design in the placing of these stones compared to simple dumping, but stones built into an early structure such as that at Lullington do not necessarily suggest that the stones originally came from the churchyard, giving no real proof for the antiquity of the site. Whatever the reasons for the stones being on the site on the site of a church, it is certainly not an uncommon phenomena in Sussex, with stones at Brighton, Aldrington, Southwick, Shipley, Steyning, Ditchling, Alfriston and Alciston (section to be added), most of which are built on hills or mounds.

Stones In Placenames As well as a simple "stone" appearing in Sussex placenames, such as at "Amberstone" and "Goldstone". Care must be taken as in the case of a seemingly stone related "Bishopstone", where the name actually derives from "Bishop's Tun", i.e. the bishop's farmstead, or "Blackstone", another farmstead. Stones in placenames can take other forms, such as "Stan-", which can be found at "Stanmer", "Stanstead", "Standean" and "Stane Street". "Steyne" is usually found relating to a rocky area of ground such as "The Old Stein" or "The Old Steyne" in Brighton and "Steyning". "Stein" (pronounced steen), probably comes from the local dialect verb, to "Stean", which can mean to pave a road with stones, line a well or grave with stones, or to mark out a field with stones for ploughing (Parish & Hall 1957 p.131). Stone itself is pronounced "Stun" in local dialect, which probably come from the Saxon word "Stæn" which appears in so many ancient place names. Boundary Stones There are hundred's of boundary stones in Sussex, marking points on the edge of a parish or manorial boundary, usually where the course of the boundary changes. While most of these are modern, either a natural stone placed in position or a concrete post, some such as the naturally occuring sarsens at Rocky Clump are more ancient. The modern stones are mostly from the 19th century when the existing unrecorded boundaries were formalised and recorded by Tithe Commissioners under the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836, who also put up new boundary stones to mark the results of their work (Winchester 2000 p.46). Before this work, the boundaries were remembered by passing on the information by word of mouth. This was usually done by great perambulations of the boundaries during Rogation Week and was generally known as 'Beating the Bounds'. This old custom, apart from the walking aspect, encompassed as the name suggests, the beating of boundary markers with sticks, and the beating of young children at these boundary markers to impress upon their memory the importance of remembering the line of the boundary. Names or initials of the parish or of a person such as the lord of the manor were inscribed on trees and on the ground and in many places were made more permanent by inscriptions on boundary stones. Sometimes you may get a pair of stones or a stone marked in two with the names of both parishes inscribed. One possibly quite old stone mentioned in tales about perambulations related to the manor of Balneath (originally Balneth) in the Parish of Chailey. The manor is thought to be land donated to the priory at Lewes after the Norman invasion by William De Warrene. The account itself, dated 1954 tells of an earlier permbulation in 1829, where the eight men who were performing the perambulation had stopped at a stone "twenty rods south of the windmill". The stone was "Marking the middle of Sussex" (Christian 1955 p.473). An equally important stone is allegedly somewhere in the vicinity of Shiremark Farm (TQ174375), which marks the border between Surrey and Sussex (Lower 1864 p.256). The use of the word shire is interesting as neither Surrey or Sussex are generally thought of as Shires, which may point to the name being quite old. Stone Circles The evidence for the existence of Stone Circles in Sussex is purely circumstantial at the moment. Some church sites such as St. Nicholas, Brighton may have been the location of stone circles, but the evidence is now lost and all we have now is old accounts from early antiquarians. We have megalithic monuments to the west in Hampshire and to the east in Kent and once had a good supply of raw material scattered on the downs and coastal plain for the construction of such monuments. But there is the problem of a lack of cultural evidence in the archaeological record. The preceding henge monuments that are spread widely in counties where megaliths abound are thin on the ground in Sussex, despite a several good examples of Causewayed Enclosures on the chalk downland from the earlier Neolithic. Nevertheless, we have a triple ringed henge recently excavated near Lavant and the rather odd henge monument on Wolstonbury Hill, along with other possible monuments of the later Neolithic period (Russell 1997 p.74). Even the stones that currently sit around the Goldstone are of dubious antiquity as they were originally sited around a pond. As has been seen at Falmer and Standean, farmers put stones where they are not in the way, and the example of Goldstone Bottom may just be another, older example of this. The only true stone circle known in Sussex lies near Ditchling and was constructed by a local farmer in modern times. |

|

| Bibliography |

|

Aitchison, George : Unknown Brighton, Bodley Head 1926 Aldsworth, F.G. : The 'Druid Altars' at Rudgwick, West Sussex, SAC Vol. 121 1983 Ashton, Chris : In Mysterious Hove: The Goldstone, QsM #2 1980 Barr-Hamilton, A. : Excavations at Lullington Church, SAC Vol. 108 1970 Beckett, A. : The Spirit of the Downs, Methuen 1943 (6th Ed.) Blair, J. : Saint Cuthman, Steyning and Bosham, SAC Vol. 135 1997 Bloxam, M.H. : Notes on Places Visited at the Annual Meeting, 14th August 1863, SAC Vol. 16 1864 Bull, W. : A Sussex Hermit, SCM Vol. 3, No. 12 1929 Candlin, L. : Tales of Old Sussex, Countryside Books 1985 Christian, Gareth : A Modern Perambulation, SCM Vol. 29, No. 10 1955 Clarke, S : S. Nicholas Church, Brighton, SAC Vol. 32 1882 Copper, B : A Song for Every Season, Heinemann 1971 Cox, E.W. : The Steyning Stone, SCM Vol. 12, No. 11 1938 E.A.M. : The Steyning Stone, SCM Vol. 13, No. 2 1939 Evans, A.A. : The Mystery Stones of Sussex, Sussex County Herald 24/03/1933 Evans, A.A. : A Saunterer in Sussex, Methuen 1935 Funnel, J. : Excavations at Rocky Clump, Stanmer, Flint No. 43 2000 Gilkes, O. : Excavations at Rocky Clump, Brighton, SAC Vol. 135 1997 Gorton, W. & Yeates, C.W. : Rock Clump, Stanmer: a Forgotten Shrine? Privately Printed 1988 Grinsell, L.V. : Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain, David & Charles 1976 Johnston, P.M. : Chithurst Church, SAC Vol. 55 1912 Jones, David : Southeast and Southern England, Methuen 1981 Hamilton, S & Manley, J : Points of View : Prominent Enclosures..., SAC Vol. 135 1997 Holden, Eric : Diary entry 19/01/1976, Sus. Arch. Soc. Working Papers, Holden 20B/8 Holden, Eric : sarsen Stones, Sus. Arch. Soc. Working Papers, Holden 12/12 Holden, Eric : sarsen Stones, Sus. Arch. Soc. Working Papers, Holden 12/13 Holgate, Mary S. : The Surroundings of Philpots Camp, SAC Vol. 67 1926 Horsfield, T.W. : The History, Antiquities, and Topography of the County of Sussex (2 Vols), Baxter 1835 Lower, M.A. : The Rivers of Sussex, Part II, SAC Vol. 16 1864 Martin, E.A. : Life in a Sussex Windmill, Allen & Donaldson 1920 Martin, E.A. : Megaliths of the South Downs, in Holden 12/12 Martin, J.E. : The Goldstone, Hove, SCM Vol. 5, No. 2 1931 Mawer, A. & Stenton, F.M. : The Place Names of Sussex (2 vols), Cam. Uni. Press 1930 Middleton, Judy : A History of Hove, Phillimore 1979 Moens, S.M. : Rottingdean, The Story of a Village, John Beal & Son 1953 Mogar, O.M. : The Half-Hundred of Fishersgate, VCH Vol. 7 1973 Pagden, Florence : History Of Alfriston, Combridges 1950 (9th Ed.) Parish, Rev W. D. & Hall, Helena : Sussex Dialect Dictionary, Gardners 1957 Russel, M. : NEO-"Realism": An Alternative Look at the Neolithic Chalkland Database of Sussex, in Topping 1997 Simpson, J. & Roud, S. : A Dictionary of English Folklore, Oxford Uni. Press 2000 Spokes, S. : Steyning "Firestone", SCM Vol. 10, No. 4 1936 Tebbutt, C.F. : The Prehistoric Occupation of the Ashdown Forest Area of the Weald, SAC Vol. 112 1974 Toms, H.S. : sarsens in Sussex, SCM Vol. 1, No. 12 1927 Toms, H.S. : The Goldstone, Hove Park, SCM Vol. 6, No. 11 1932 Topping, P : Neolithic Landscapes, Oxbow Monograph 86 1997 Wales, Tony : Sussex Ghosts & Legends, Countryside Books 1992 Winchester, Angus : Discovering Parish Boundaries, Shire Publications 2000 |